Article from

ONCE UPON A TIME DAD

My great love affair with the Western. Horses, buffalo, cowboys, Indians, the Great Plains, stagecoaches, deserts, campfires, harmonicas, forts, Apaches, peace pipes, treachery, Death Valley, the Grand Canyon - the whole mythology of the American West has always fascinated me.

And as my psychoanalyst had repeatedly explained, there was always a reason for what happened to us, an obsession. As a child, left to my own devices by my parents on a sofa while they worked hard, I learned to watch the western films shown on Tuesday evenings during La Dernière Séance presented by Eddy Mitchell. The process was always the same: I finished my homework, made buttered pasta for myself and my sister, put her to bed, put her to sleep and when that was done, I turned on the television and immersed myself in the wilderness. Thanks to Eddy I was able to discover films that marked me for life: Broken Arrow, Little Big Man, Johnny Guitar, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Winchester 73, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon... all great art that opened my eyes and my heart while leaving my little girl's soul in place to delight in the two Tex Avery films that followed.

And when I wasn't too tired, I'd watch the second film, often for a more adult audience. So I built up a solid Western cinephilia, which reflected on me the following days in the playground. I used rubber bands as lassos and I'd stuff anyone who dared to take me on like a roast. If I was offered the chance to play cowboys and Indians, I always chose to play the role of a Sioux chieftain. This allowed me to use spells and cast evil spells that sometimes became real. How many of my comrades ended up with ferocious herpes outbreaks because I wanted it so badly? So much so that the school was very worried and ended up threatening me with expulsion if I didn't stop my bewitchments. The rest of my schooling went smoothly. I was a good pupil, hard-working, and in the evenings I looked after my younger sister. My extra-curricular activities revolved around dance. Classical first of all, as I was a little rat at the Opéra. And at the weekends, Saturday nights to be precise, if my father wasn't working, I'd ask him to come with me to a club where they played country music so I could do a few steps and learn to line dance. Unlike my friends, I didn't smoke tobacco, I chewed it. And I did all my end-of-year courses on farms. I'd started riding and I made sure I did it at least three or four times a week. It simply ate up my time. So much so that, at one point, I thought I'd have to combine all these activities to pursue my passions at the same time. I was getting ready to become a farrier, but then my father fell ill. Suffering from depression, he stopped all his professional and personal activities. He was bedridden and wanted only one thing: to die.

Suddenly, the world stopped around him. I put aside my desires, my mother her passions, her work, my sister her studies and we all took turns at his bedside to ask him what would get him out of his condition and his answer invariably came back: leave. And no molecule on the pharmaceutical market could do the job. We tried everything. I even thought of invoking spells again. My mother, in a strange burst of lucidity, thought that maybe someone could wake him up from his torpor. She put her network to work and, after passing through the sister-in-law of her brother-in-law's cousin, managed to get him a personal concert with the greatest crooner in North Africa, Enrico. He agreed to come and play some of his greatest songs. And as he had only done four or five, it didn't last very long. But my mother's shakshuka (sorry for spelling it like that) was so good that he played his repertoire several times, just to get more of it. We had naively thought that, being from the same village as Enrico, my father would have risen from the depths of his depression, but alas, three times alas, he never batted an eyelid during the songs of Constantine's Franck Sinatra.

The rest of his illness was worse. At that point, he could only express himself through sounds, grunts to say yes, no, eat, drink. In desperation, and because after all it was he who had planted me as a child in front of westerns as a nanny, I decided to take him, with or against his will, to get to know the Death Valley. What better place to visit for someone who wanted to die? I strapped him into a wheelchair, because he didn't want to walk, and popped him full of sleeping pills to take him, by myself, over the ocean and most of the United States. When we arrived, I removed his blindfold so that he could see the crater of the Ubehebe volcano. It was absolutely breathtaking and touched his heart instantly. So much so that he stood up from his wheelchair. He hadn't set foot on the ground for weeks. His legs were shaking, but I told myself that this was the long-awaited beginning of his remission. I hired a small cart afterwards and we travelled with a team of two horses. We passed by Dante's View, where the sunset made an indelible impression on our retinas for the rest of our lives. His legs were shaking but I told myself that this was the long-awaited beginning of his remission. I hired a small cart afterwards and we travelled the road with a team of two horses. We passed by Dante's View, where the sunset made an indelible impression on our retinas for the rest of our lives. We continued on to Zabriskie Point and then Natural Bridge, where we camped for three whole nights. My father played with the coyotes and kept us safe from the rattlesnakes that were hanging around a little too close to our camp. We had an incredibly profound time. We said very little. But we cried a lot at such beauty and at being together in a silence of total fulfilment. We felt good.

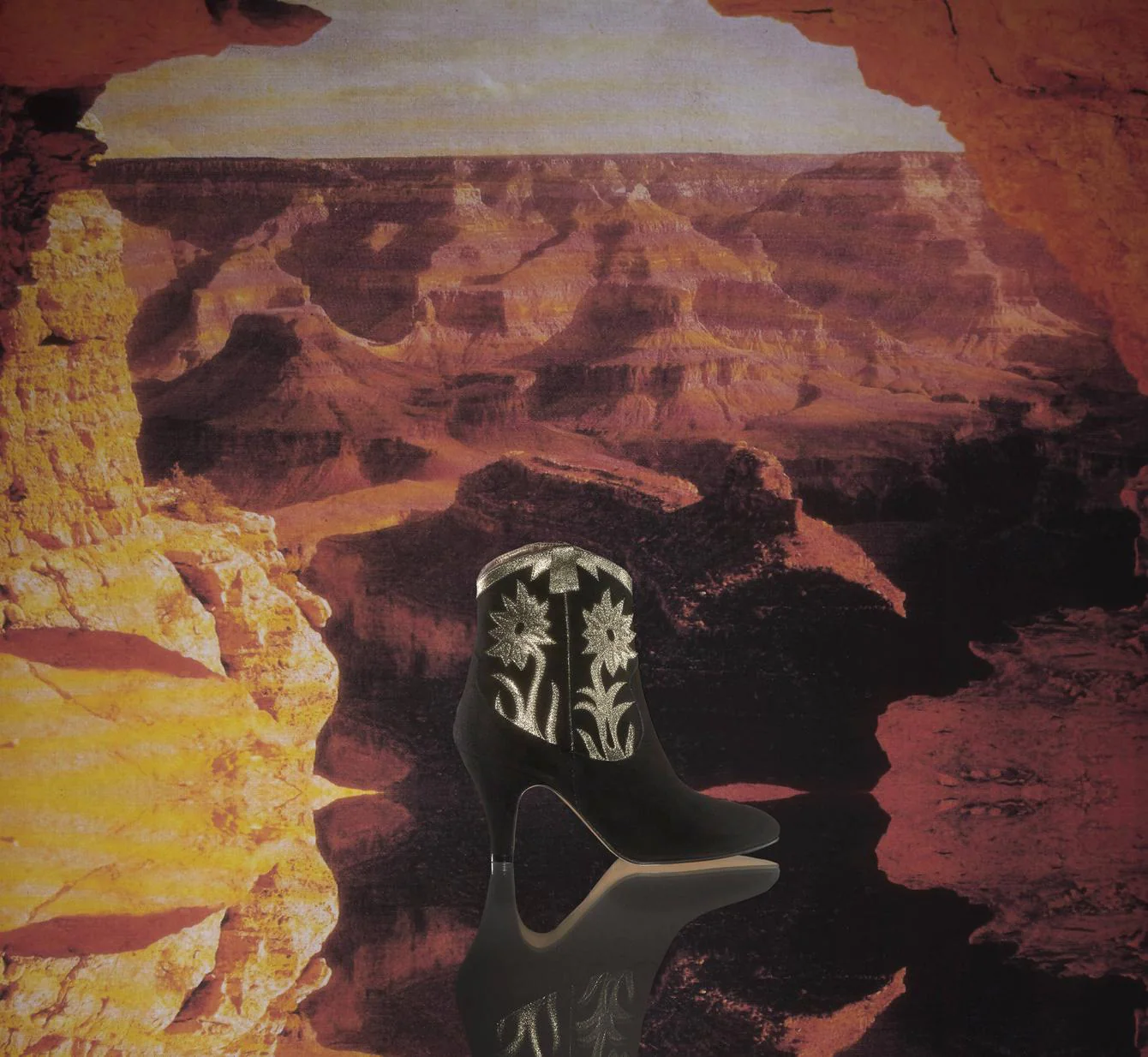

Even on his deathbed, my father told me about the incredible trip we had taken twenty years earlier. He spoke of it with great emotion, as one of his fondest memories that took away any death wish. So, in order to let him leave peacefully, without robbing him of the slightest joy or illusion, I didn't dare tell him that I had drugged him heavily throughout the journey and that I had, in fact, taken him to the Mer de Sable at Ermenonville, a park that revived the great themes of the Conquest of the West. What he thought were coyotes were in fact stray dogs, and the Volcano Crater was nothing more than a gaping hole in a rubbish dump next to the park. But I'd put so much pressure on my father that he thought he'd crossed the Atlantic, and that was all that mattered, because he'd come out of his depression and we'd found him even stronger. That's why, years later, when I imagined the Angel, Letterman model, with its 'western' soul, it was in memory of my daddy, my little angel who had left too soon. A tribute, as I always do in all my creations.